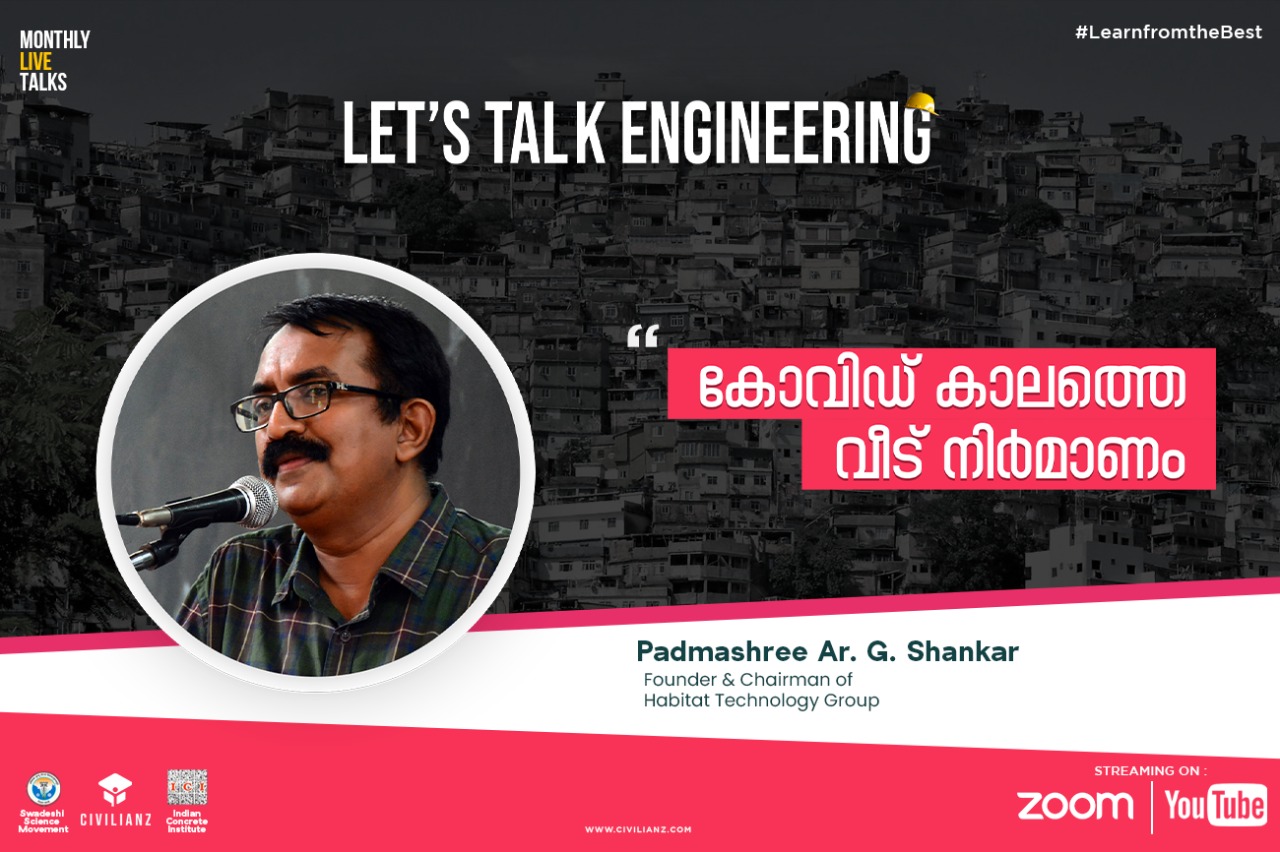

LET’S TALK ENGINEERING :Episode2 , പരിസ്ഥിതി സൗഹൃദ വീടുകളുടെ പ്രചാരകനും, ഹാബിറ്റാറ്റ് ടെക്നോളജി ഗ്രൂപ്പിന്റെ സ്ഥാപകനുമായ പത്മശ്രീ ജി. ശങ്കർ ഈ TALK SERIES ൽ നമ്മോടു സംവദിക്കാനെത്തുന്നു.

വിഷയം : കോവിഡ് കാലത്തെ വീട് നിർമ്മാണം

LET’S TALK ENGINEERING :Episode2

ആർക്കിടെക്ചർ രംഗത്ത് ഗ്രീൻ ആർക്കിടെക്ചറിലൂടെ പുത്തൻ സാധ്യതകൾ തുറന്നു കൊടുത്ത People’s Architect നോടൊപ്പം അദ്ദേഹത്തിന്റെ വിലയേറിയ ആശയങ്ങൾ ശ്രവിക്കാൻഎല്ലാവരെയും ക്ഷണിക്കുന്നു.

A joint venture by Civilianz l& Swadeshi Science Movement in association with Indian Concrete Institute – Trivandrum Chapter

# LET’S TALK ENGINEERING :Episode2

ABOUT THE PEOPLE’S ARCHITECT | Padmashree G Shankar

For over three decades, Padma Shri recipient Gopal Shankar has been at the forefront of sustainable architecture in not just India, but around the world.

Starting the Habitat Technology Group, the largest non-profit in the shelter sector in India committed to sustainable building solutions, cost-efficient, community-driven and eco-friendly architecture, Architect Shankar has been at the forefront of constructing nearly 1 million mass housing units (and over 100,000 green buildings) in more than five countries.

From constructing the first township built with green building technology in India, which contains 600 houses, a community centre and temple, in Sirumugai, Coimbatore in 1995 to the largest earth building in the world measuring over 600,000 square feet in Bangladesh in 2006, Architect Shankar has religiously taken on the cause of sustainable architecture with his blood, sweat and tears, battling hostile contractors, the establishment and naysayers.

More importantly, however, from his office in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, he has empowered those living on the margins to build quality homes with their meagre resources. Today, vegetable vendors and traditional fishermen in the city come to his office to design their homes. The masses of this country have an architect they can approach.

Design philosophy

For Architect Shankar, the design of any building must rest on some fundamental people-centred and value based parameters—eco sensitivity, cost efficiency, energy efficiency and disaster mitigant. This naturally translates into how he selects his material and equipment.

“My focus is on the local availability of any material. This is fundamental and the platform upon which you develop a sustainable design. Local materials and resources are critical components of sustainable development. With local material comes utilising local capacities to build the structure. Another key factor is eco-sensitivity. Any material that does not fit this mould is unacceptable. Finally, the material needs to be both energy and cost efficient as well. These are the basic factors I take into account. When I build in Kerala, for instance, I look at bamboo because it’s locally found and meets my strength requirements. It is a significant replacement for steel, matching its tensile strength,” he says.

Another material that Shankar often uses is lime. Kerala has one of the largest deposits of lime in the world, and it is a real replacement for cement, he says.

“See, cement and steel eat up a lot of energy during the production process. That is why we are trying to stay away from them. Instead, we are using earth building material, which is both cost effective and cools your home. My own office, which is a six-storeyed building, is completely made of earth. While people have a torrid time outside the office during summers, it is really cool inside,” adds Architect Shankar.

Before earth, it was exposed brickwork. However, more than 15 years ago, he realised that brick isn’t very eco-sensitive because making it requires burning a lot of wood. That’s when he turned to materials like earth. Although weaknesses exist, he has made upgrades to it.

When choosing a project to work on, the famed architect does look at the basic physical requirements like climate, environment, vistas, terrain, accessibility and connectivity, among other factors. However, what sets him apart is that he also ascertains other needs of the person he’s working for. Whether the person wants a place to read, meditate, listen to music, sing and a place to sit alone and look at the sky find their way into the design.

“I talk to them, and get a sense of who they are. My homes are not built in cement and mortar, but love, affection and compassion,” he says eloquently.

Take the example of G. Shankar’s mind altering house of mud at Mudavanmugal, a perfect example of architecture that is in sync with nature. Called ‘Siddhartha’, it is a uniquely shaped mud house crafted with a parabolic design idiom which has beautiful creepers and bamboo growing out of it.

Why Habitat Technology Group?

Architect Shankar grew up in a state, which had completely forgotten the legacy of vernacular architecture. With money flowing in through remittances from the Middle East, people were building what he calls ‘monstrosities’ that did not factor in their cultural heritage, local structural nuances and the environment.

“I believe in the goodness of indigenous architecture because they always belonged to the site and the people. Traditional architecture involves 1000 years of research and development. The legacy of residential architecture in Kerala is huge and it has developed some of the most profound styles. Looking at the physical, social and cultural climate, their concerns were so widespread and beautiful,” he says.

For him, these ‘monstrosities’ represented the proliferation of greed and power. After an uninspiring stint in Delhi, following university in the UK, he came to work for the Kerala government. However, he soon realised that they weren’t on the same page, and soon made a beeline for the voluntary sector.

“I wanted to build a people’s movement. The ordinary people of Kerala were looking for options beyond these ‘monstrosities’,” he says.

Starting out as a one-room one-person organisation in 1987, it was six-month wait before he was commissioned his first project, a small house for a bank clerk. However, the following years saw exponential growth. By 1990, he was doing 1,500 houses a year. # LET’S TALK ENGINEERING :Episode2

Disaster Rehabilitation

For over three decades, the Habitat Technology Group has worked with State agencies, other non-profits, corporations and local volunteers across multiple disaster-affected zones, helping people rebuild their homes abiding by his design principles.

From rehabilitating hundreds of families following the Bhopal Gas Tragedy to rebuilding homes following the Super Cyclone in Odisha in 1999 and Sri Lanka after the devastating Tsunami five years later, the Habitat Technology Group has done some remarkable work.

However, following the devastating Kerala floods last year, the State government took the route of building prefabricated houses for those who had lost their homes. For Architect Shankar, this isn’t the right solution and believes a lot more can be done.

“They talked about prefab housing solutions for the poor. I said ‘no, we need to build people-centric homes’. The government of the day didn’t understand the language of sustainability. On my own, I’m tying up with multiple CSR initiatives, including Aster Homes, building up 1,000 homes for the homeless. In another two months, we are looking to build up another 500 homes. It’s almost been a year since the disaster, but we haven’t learnt from it. I’m a skeptic, but I also dare to dream for a sustainable future,” says Architect Shankar.

Leave a comment